"It wasn't me that made him fall No, you can't blame me at all" Who killed Davey Moore Why an' what's the reason for?

Boxer's death inspired change in the fight game

Kevin Modesti, Los Angeles Daily News Ê San Fransisco Chronicle, Friday, July 27, 2001 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Los Angeles -- FOUR DECADES after his death left a bloody mark on the otherwise gleaming image of Dodger Stadium, Davey Moore's name means different things to different people. To Bob Dylan fans, it's a song lyric. To the anti-boxing crowd, it's a rallying cry that inspired abolition demands and prompted safety-rule changes. To old-time fight fans, it's a bittersweet memory of a good man and popular champion lost to an unimaginable fate. So when Roy Jones Jr. defends his light heavyweight title tomorrow at Staples Center -- it's a reminder that this sport has a way of leaving behind unwanted memories. "(It) has never been done before! Three world championships in our city!" Los Angeles City Councilman Nate Holden crowed Wednesday at a news conference to promote this week's Staples Center card headed by Jones vs. Julio Gonzalez. But, in fact, it has been done in Los Angeles at least once: On Thursday, March 21, 1963, 1-year-old Dodger Stadium played host to title bouts matching featherweight champion Moore against undefeated No. 1 contender Ultiminio "Sugar" Ramos, welterweight champ Emile Griffith against No. 1 contender Luis Rodriguez, and welterweights Battling Torres and Roberto Cruz for the vacant title. Scheduled for March 16, the card was postponed after wind-blown rain turned the ring set atop the pitcher's mound into a giant sponge. The 5-foot-2 1/2 Moore, at 29 and in the fourth year of his title reign, was having trouble getting down to the featherweights' 126-pound limit. Nobody involved could claim ignorance of the dangers involved. Griffith carried the stigma of having killed Benny Paret in a March 1962 match at Madison Square Garden. A boxer named Alejandro Lavorante lay dying in an L.A. hospital as the result of a September 1962 loss to Johnny Riggins at the Olympic Auditorium as he tried to bounce back from knockouts by Cassius Clay and Archie Moore. But nobody could imagine that happening to Davey Moore, the "Little Giant" from Springfield, Ohio. Though he no longer wore the aura of invincibility, having lost six times in 62 pro fights, he had the aura of indestructibility. The "tripleheader," hailed by writers of the day as the most ambitious boxing program ever presented in California, drew more than 26,000 fans paying $5 to $30. Moore-Ramos went on between Griffith's 15-round loss to Rodriguez and Cruz's first-round knockout of Torres. Moore dominated the first two rounds of the scheduled 15. "The fight had begun as a study in politeness," columnist Melvin Durslag wrote. "At the end of each of the early rounds, the boys did more than touch gloves in the sometimes friendly custom of the sport. They threw their arms around each other as if greeting an immigrant cousin. "All the while, a savage war was developing." Ramos, a 21-year-old Cuban living in Mexico City, took control to the delight of the largely Latino crowd. In the 10th, Ramos' left hooks sent Moore into the ropes. A series of Ramos lefts and rights drove Moore toward the center-field side of the ring, where a left hook knocked him onto the seat of his shorts, his head twanging against the lowest of the three ropes. Moore got up as referee George Latka counted "three," and that rope wouldn't be given another thought for days. The bell ended the 10th as Ramos' right hand left Moore slumped over the middle rope. Latka was marking his scorecard when Moore manager Willie Ketchum signaled that his man couldn't go on. Nothing appeared to be wrong with Moore, especially in the estimation of Moore. He walked to the dressing room and talked for 40 minutes. "Sure, I want to fight him (Ramos) again," he said, a bloodshot left eye his only apparent damage. "And I'll get the title back." The reporters had left when, as friend and sparring partner Ronnie Wilson described it later, Moore put his hands to his head and said, "Oh, my head aches." He slumped into unconsciousness. His wife, Geraldine, who never attended his fights, arrived at White Memorial Hospital after midnight to hear that Davey had a bruise and swelling at the base of the brain and that surgery would do no good. Moore never regained consciousness and died March 25. "It is God's will," Geraldine said after being awakened with the news. Then she fainted. Their five children were at home in Ohio. Neurologists determined the injury could not have been caused by a punch. Viewing a videotape of the fight, they focused on Moore's fall against the bottom rope late in the 10th round. In what a doctor called a "million-to-one" accident, the rope had struck Moore like an expert karate blow. California Gov. Pat Brown asked the legislature to ban "this so-called sport." The Vatican newspaper condemned boxing as "morally illicit." Dylan's 1964 song, "Who Killed Davey Moore?" skewered all of boxing -- from "the referee" to "the boxing writer" -- for trying to avoid blame. Moore's death changed boxing only slightly. California officials ordered ring ropes padded, a fourth rope added and the bottom rope loosened in an attempt to prevent similar damage from a fighter striking his head, said Johnny Flores Jr., whose L.A.-based MasterBuilt Boxing Ropes and Equipment built the Staples Center ring. In many small ways like that, boxing has been made safer over the years. Men continue to die in the ring but not as often as four decades ago.

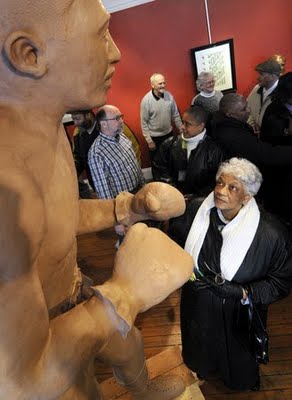

Geraldine Moore, the widow of boxing champion Davey Moore, stares up at the bigger-than-life sculpture of her late husband after it was unveiled at the studio of artist Mike Major. Major is in the background, at left, talking to Moore's family. From Ed Ricardo, 2009